Summer with Monika Review: Unravelling Love’s complexity in Summer With Monika

‘Parting is such a sickly sweet sorrow, let us not think about tomorrow’ - Summer with Monika delicately handles what it means to love and be loved through an ambitious, multifaceted storytelling approach.

Summer with Monika fundamentally captures the multifaceted nature of love and its challenges through an entirely ‘real’ - or human - perspective. The play commences with an idyllic portrayal of the ‘honeymoon phase’, where even the most mundane elements of a relationship are imbued with a sense of romanticism. However, as the narrative progresses, the script gradually moves away from more abstract metaphors of love to intricate, or perhaps accurate, explorations of human affection - and crucially - wanting. In doing so, the play offers the audience a comprehensive view of human connection, oscillating between moments of authenticity, tenderness, jealousy, pillory, and the enduring ennui that can often shadow prolonged relationships.

The piece itself finds its origins in a collection of love poems by Roger McGough, initially inspired by Ingmar Bergman's 1953 film. This interplay between poetry and drama offers a perennially intriguing challenge for directors, who must balance the preservation of poetic essence with the presentation of a coherent narrative.

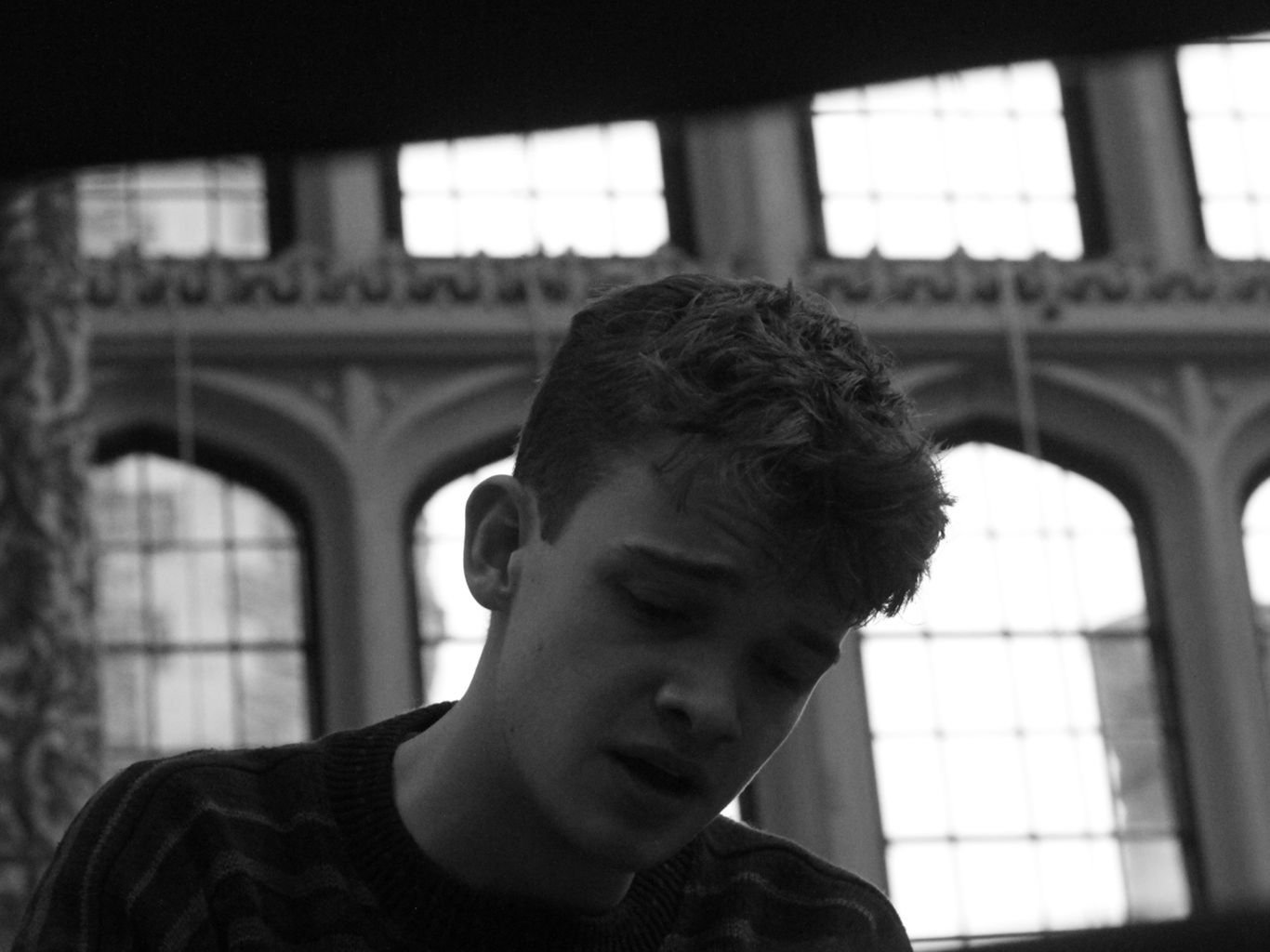

From the very outset, it became apparent that director Daisy Shaw, in collaboration with Jules Coyle and Aaron Gillett, had thoughtfully embraced this challenge. Indeed, it was a pleasure to observe the realisation in Shaw’s Director’s Note: ‘it just seems to ask to be read out’. McGough's words, in the capable hands of Jay Palombella, breathed life into a dynamically evolving dramatic monologue, delivered with remarkable fluency and poise.

Prior to Palombella’s entrance, the audience were immersed in an atmosphere reminiscent of an impending concert. This ambience owed much to the central stage, where Shaw had placed a band. This ensemble included Max Pullinger, the Musical Director, who also played piano and bass, alongside Charlotte Lampe on drums, and Robert Allen and Chloe Fisher on guitar. Their positioning made clear their role in animating the forthcoming performance. The ingenious addition of live music punctuated Palombella’s narrative with a delightful rhythm and pace, shifting seamlessly between more sombre compositions and universally recognised love songs, including Van Morrison's timeless classic, "Brown Eyed Girl."

When Palombella took the stage, he found himself in what appeared to be a bedroom or living room, thoughtfully designed to evoke the aesthetic of the 1970s, complete with a record player and picnic basket — a subtle but transportative touch by Maddy Guha and Sarah Cunningham.

It seems important to note, that on my way to the theatre, I was considering how mammoth a task a continuous 40 minute monologue is; demanding substantial proficiency from director and actor alike. This was a challenge that I felt Shaw handled beautifully, who adroitly partitioned Palombella's narrative into discrete segments by using subtle staging techniques to maintain the performance’s dynamism and continuity.

A particularly poignant moment came when Palombella, swaddled in a blanket, reclined upon his 'had-been-happy bed,' evoking a sense of childlike vulnerability, compared to his earlier, more brutish characterisation. Until this point, the empty bed was symbolic of a once fertile ground for the protagonist and his lover. Yet, Palombella’s movements seamlessly transformed this piece of furniture into a quasi-chaise longue, the kind found in a psychiatrist's study. This introduced a brief interlude in the audience-protagonist dynamic, casting the viewers in an almost therapeutic role as they observed Palombella’s emotional turmoil. Thus, clever staging made a once romantic sanctuary entirely clinical, and a once removed audience entirely involved.

Indeed, throughout the performance, subtle and symbolic motifs made fleeting appearances, their nuances requiring keen observation. Notably, knives, the sole pieces of cutlery within the picnic basket. Their glinting presence, accentuated by the lighting, presaged the protagonist's irrational and jealous contemplations regarding Monika's supposed infidelity. This mise en scène fostered an undercurrent of foreboding, underscoring the complex interplay between love and violence — a central thematic tension within the play.

If I were to take any one thing away from the play, other than Palombella’s careful confidence or Shaw’s ambitious innovation, it would have been how the play conveyed the significance of objects and their mutability or permanence. It was particularly noteworthy that the protagonist's climactic interruption of the band at the denouement underscored their role as instrumental elements in his narrative, much like the rest of the set. In this final act, the musicians themselves become conduits within the broader orchestration of the story, imparting depth and complexity to the exploration of love's capricious nature.

Summer with Monika is on at Pembroke New Cellars until the 28th of October.