Pain in Reproductive Care Shouldn’t be Routine

Why should we have to ‘tolerate’ medically avoidable pain?

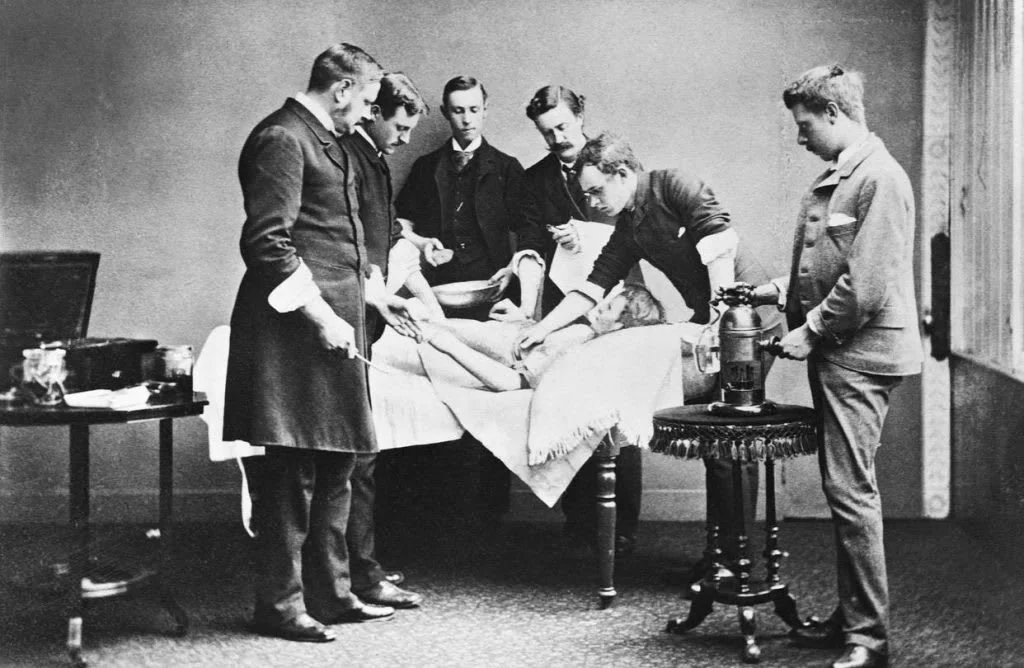

Six months ago I made the decision to get an intrauterine device fitted. In a 2012 article (coincidently about mistakes made by GPs whilst fitting these devices) it was estimated that 127,000 people in the UK have one fitted in a year period. The IUD tends to be an option someone goes for if the first line of defence – the much beloved Pill – does not work, either for the myriad of issues it is prescribed for (too many hormones, too few hormones, too much emotion, too much blood etc) or because it is less anxiety inducing to be off it and at risk of pregnancy, than it is to take it and put up with a plethora of often debilitating side effects. What I’m essentially trying to say is that nobody chooses to have their uterus palpated, their cervix dilated and a piece of plastic adhered to their uterine wall on a whim.

So on the hottest day of the year, I find myself sat with my partner in the doctor’s treatment room. She asks a series of vaguely excruciating questions – when you last had sex (do you want days or hours), when was your last period (let me pull out my aesthetically pleasing tracking app), can you be sure you’re not pregnant (I have clinically diagnosed OCD, I can never be sure of anything). I’m asked to strip off up to my belly and lie down on the bed, covering myself with a thin sheet of blue paper (a surreal, dreamlike experience). What follows is not pretty; if you are uncomfortable with graphic descriptions of genital-related phenomena I would suggest you don’t read on. I write this explicitly not for shock value but because I fear the point I am trying to hammer home will not hit its destination if I do not. I should disclaim that I completely trusted the nurse and doctor who performed my procedure. They made sure at every point that I knew I was in control, that they would stop touching me if I asked, that they could stop the procedure at any point. I had someone holding my hand throughout, and who looked after me as I writhed in pain for the rest of that day. I have no lasting trauma from the experience, except a memory of that pain and a more insidious anger that I had to experience it, when it was medically possible for me not to.

After inserting both her fingers and a speculum inside me, the doctor informs me that I have a retroverted uterus – a fairly common phenomenon affecting around 25% of people with the anatomy. She follows this up with an observation that this can cause painful periods and uncomfortable sex. A lightbulb clicks on inside my head. Nascent explanations for previous experiences begin to form themselves; I feel as though my memories were expanding and settling with this new clarity about my body. But just as those thoughts begin to settle into expressible truths, I feel a sharp, tugging pain deep in my pelvis as a tenaculum is clamped over my cervix. It is at this point that I cry out and am offered local anaesthetic gel. I’d previously been informed that I had to advocate for this, but had not been told at what point in the procedure I was allowed to ask for it – and, quite frankly, it does very little. Once the procedure is over (and I’ve been told I’d ‘tolerated my pain well’ – this fact is even written in my medical notes), the aftereffects set in. I stumble home nauseous and teary to lie, sweating, in bed for the rest of the afternoon.

I want it to be clear that I do not regret getting this procedure. I have struggled with a myriad of menstrual related problems since I got my period at fourteen, and wanted an effective form of contraception. The problem here is not regret; it is more insidious and structural.

There are around 1.2 million c-sections performed per annum in America, an estimated 100,000 of which result in moderate to excruciating pain for the person giving birth. During the second season of the New York Times’ podcast The Retrievals, women report feeling ‘everything’ during the births of their children – every cut, every pull, every tear taking place deep inside their abdomens. The National Institutes of Health consider the c-section to be ‘the most common and safe surgical procedure in the United States’ – yet hundreds of thousands of women are leaving hospitals each year with an infant and deep-seated somatic and psychological trauma. To learn more about this specific phenomenon I would suggest you listen to the podcast, both seasons. But for the sake of this essay, the important truth these cases highlight is that there is a belief that the pain experienced during reproductive procedures – c-sections, egg retrievals, IUD insertions – is necessary, expected, and to be tolerated. The consequences of these procedures, whether they be a healthy infant or the lack of one, are considered to eclipse in its entirety the pain of the procedure in the first place. I deliberately use the word pain only – instead of discomfort or pressure – because whilst all might be experienced, only the latter two are words commonly used by medical professionals to describe the experiential nature of the surgery or procedure.

“women report feeling ‘everything’ during the births of their children – every cut, every pull, every tear taking place deep inside their abdomens”

In researching this essay I sent a message out on my Instagram asking for people’s thoughts on the topic of gynaecological pain, as well as their experiences. The result was sort of unprecedented. I received messages and voice-notes from people detailing varied experiences of abortions, IUD insertions and other gynaecological procedures; one voice-note that stuck with me particularly was someone who said she’d had an IUD insertion so painful it had left her curled on the floor vomiting; the nurse looking after her had explicitly disbelieved her pain throughout. Hearing these stories further confirmed to me the expansive nature of this issue; I wasn’t imagining the pain, I wasn’t exaggerating.

“I wasn’t imagining the pain, I wasn’t exaggerating…”

Because what I felt was pain, not pressure. I ‘tolerated’ it in that the procedure was finished – I knew for health reasons it had to be so I cried and gritted my teeth – but I do not feel pride at this fact. I do not feel superior to people who, with their legs spread and genitals exposed were penetrated by a series of sharp objects in an unfamiliar room by an unfamiliar, albeit kind, doctor, did not ‘tolerate’ this pain and refused to finish the procedure, or who screamed, or swore, or generally tolerated the process but not ‘well’. What I feel is anger. Not at my doctor but at the medical climate that did not consider the procedure painful or invasive enough for me to be offered general anaesthetic, or stronger local. I’m angry that the common response to this statement would be to cite the relative safety of the procedures (around 1-2 per 1000 IUDs perforate the uterus upon insertion) or how in most cases, little to no pain is experienced (based on the statistics above, only around 0.08% of c-sections in the states cause pain). ANY pain is TOO MUCH pain. My body is sacred. My body does not deserve pain if it can be easily and safely avoided. My body does not deserve the risk of permanent psychosomatic trauma, however low that risk, if there is an option by which it can be avoided for certain (and on n a very basic, cosmically injust level, I deserve to be able to fuck without having to experience pain in order to do it safely, in order for it not to ruin my life). This doesn’t even take into account the huge number of cases in which pain is experienced but not reported, experienced but not believed, and so not metabolised into a statistic.

What I hope this piece does do is throw another story into the melting pot, and make anyone reading consider what people with specific categories of bodies are expected to tolerate to have children, to not have children, to not bleed, to feel emotionally stable, to exist without pain – and to begin to consider a medical future in which this pain is acknowledged, respected and treated in line with its emotional and physical gravity. Because that future is not only possible, its essential.